The Pineapple of Ancient Assyria

The perplexing story of a fruit that probably never existed.

By Forrest J.H.

It appeared in ancient Mesopotamia, Pompeii and Egypt.

By all reasonable historical accounts, it did not.

Before the sixteenth century of the common era, a pineapple showing up anywhere other than the land that is modern-day Brazil would explode some of the most central understandings of human history.

Yet, it seemingly appeared in art of the so-called “Old World” going back thousands of years. Some see it as proof of interoceanic trade long before the era of Columbus and global empire, something widely considered impossible.

More likely, these ancient Old World pineapples are the products of exaggeration, biased perception and genuine mistake.

FEAST FIT FOR A KING

King Sennacherib was a champion of truth, a practioner of royal justice, and a ruthless lightning-wielding military campaigner. Returning from just one of his many brave victories in armed conflict, he ordered built the Palace Without a Rival. It would be a magnificent expression of Sennacherib’s greatness, according to how he wanted it to be remembered. As the fourth king of what is known today as the Neo-Assyrian Dynasty, Sennacherib observed the family traditions of hosting lavish banquets, inspiring magnificent architecture, and attempting to abritrate his legacy for all of history. While Sennacherib’s workers molded the bricks for his unrivaled palace, he would have kicked back with a vat of ancient Mesopotamia’s finest beer and enjoyed a procession of delicious tributes.

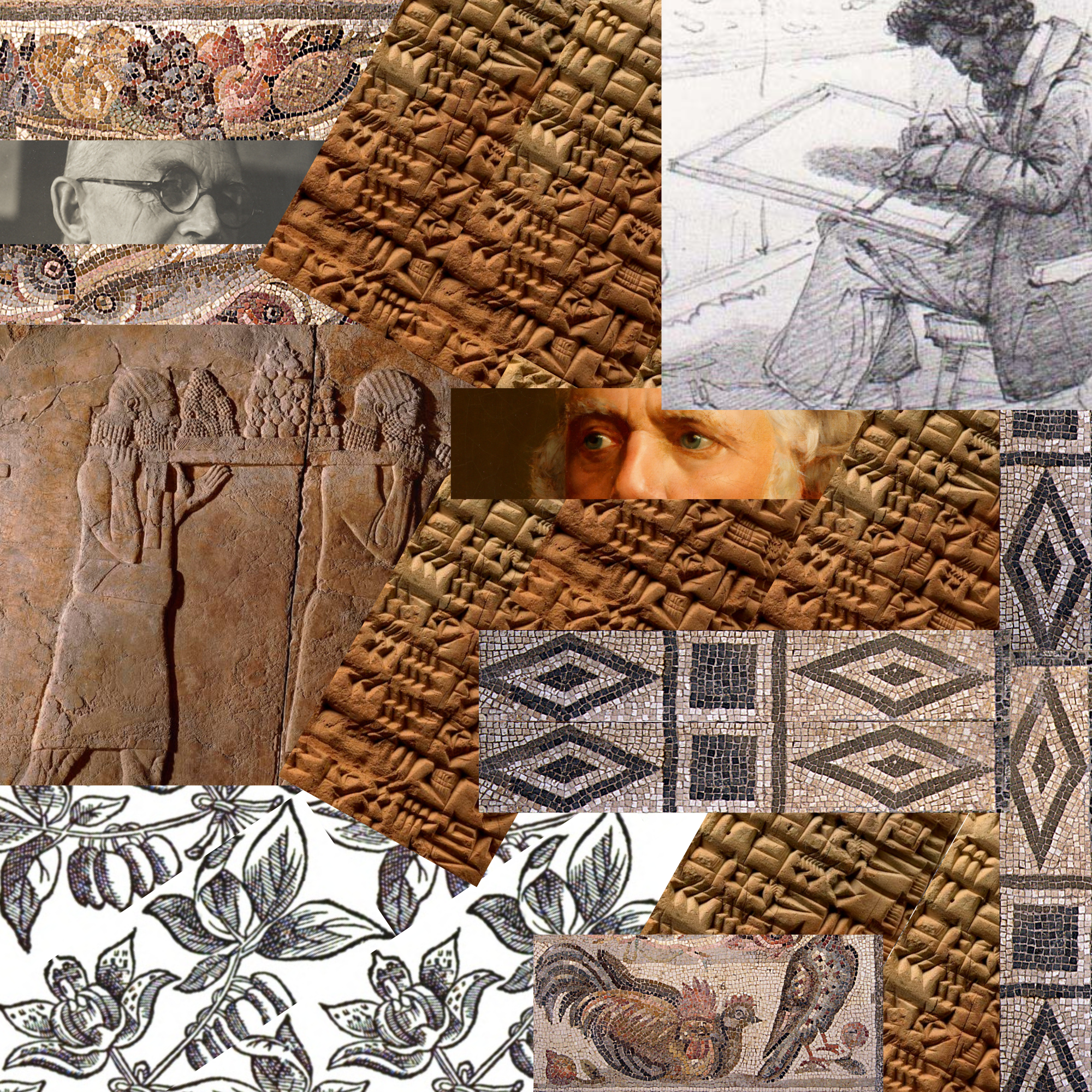

Bringing tributes to King Sennacherib c. 704-681 BCE (From the British Museum).

Beautiful scantilly-clad men with gorgeous curly hair falling on their shoulders came to King Sennacherib carrying baskets of the ripest dates and pomegranates, freshly hunted hares and partridges, expertly preserved locusts, among many other things in an epicurean feast rich with symbolism. He ordered a sculptor to record the occasion, carved in gypsum. About 2,000 years later, British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard and a team of Iraqi excavators brushed millennia of sand off of that sculptor’s work. Layard described mythical mace-bearers leading the tribute to Sennacherib.

“The first servant following the guard bore an object which I should not hesitate to identify with the pineapple,” Layard wrote in 1853, “unless there were every reason to believe that the Assyrians were unacquainted with that fruit.”

One blaring reason to believe that the Assyrians were unacquainted with that fruit, according to today’s historical understanding, is that fruit would not appear in the Middle East for another couple thousand years when European merchant colonists brought it to the Old World from its native South America.

‘AT LEAST ONE BOTANIST HAS ADMITTED’

About 800 years after King Sennacherib’s scultor carved the opulent scene in gypsum, a Pompeian mosaic artist tediously pieced together shards of colored glass to create a picture of a most elegant meal. Plump poultry, fresh fish, succulent figs and grapes – and a pineapple.

“A ‘pineapple’ has been identified in a Pompeian mural, and here again, although the pineapple was unknown in the Old World at that time, the resemblance is striking,” wrote food historians Dan and Patricia Brothwell in their 1998 book Food in Antiquity. “At least one botanist has admitted that the picture is certainly based on a pineapple, concluding that Roman traders must have brought it back from one of the Macronesian Islands with which they were possibly acquainted.”

This is an astounding assertion.

The Pompeian mosaic, supposedly featuring a pineapple in the top right corner. (From Wimikimedia Commons)

More than a millennium before the seminal and cataclysmic 1492 moonshot across the Atlantic, sailors on the coast of modern-day South America conquered an even greater distance to land in the southern Pacific Islands. They would have brought with them pineapples and their seeds as well as agricultural knowledge to enable the spread of the “New World” fruit through Asia, to a courtyard in Pompeii, or maybe even King Sennacherib’s palace, or an Egyptian tomb.

But regarding the Egyptian tomb, the Brothwells write, “doubts were later cast upon this theory.” And as for that “one botanist” who “admitted” the Pompeii mural featured a pineapple, a closer look at his interpretation says otherwise. Then there is King Sennacherib’s palace, supposedly the only one in millennia of Assyrian history to see the likes of a pineapple.

How is that possible?

LOST IN THE LIBRARY

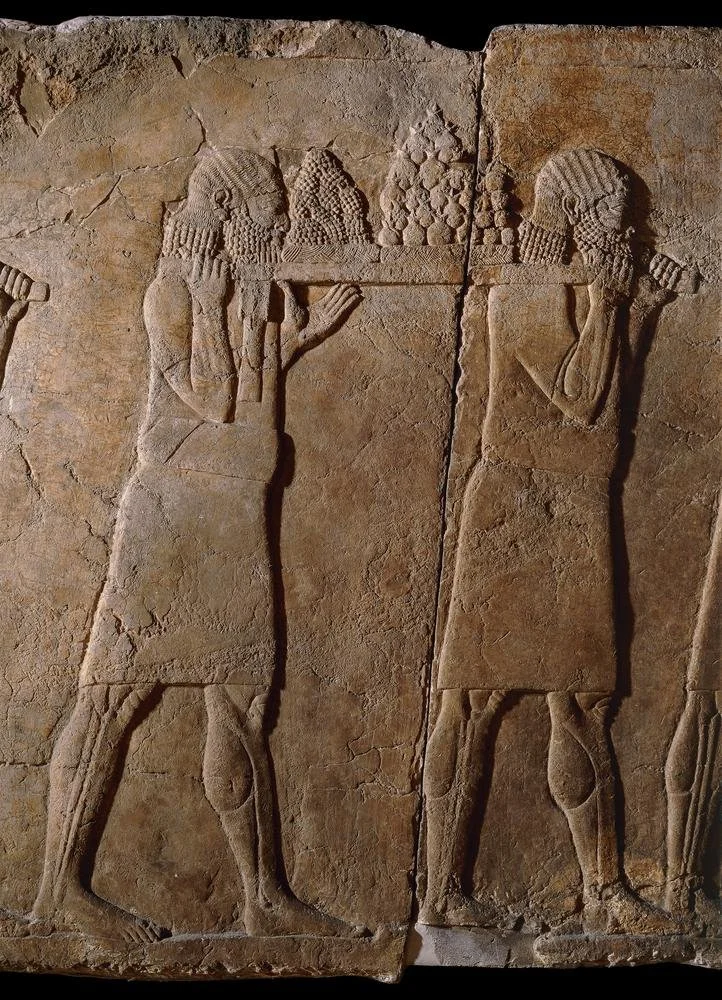

I went to the University of Virginia’s science and engineering library looking for more information on the pineapple of Pompeii. The botanist referenced in Food in Antiquity was Elmer Drew Merrill, an American born in 1876 who the New York Botanical Garden once called “the foremost contributor to the taxonomy of the plants of the Far East.” I hoped to find his description of the Pompeii mural, and how it might have ended up featuring a pineapple, in his 1954 book The Botany of Cook’s Voyages and its Unexpected Significance in Relation to Anthropology, Biogeography and History. I just had to find item QK1 in section C4. A visibly exhausted undergraduate student brought me to a narrowing marble staircase that led down to a basement entrance strangely right in the center of the building. I desperately wanted not to bother her so I thanked her, left her behind, and entered the labyrinth a little hunched with a hand over my head to avoid bonking the creaking crackling pipes above me.

Botanist Elmer Drew Merrill (From the Harvard Arboretum).

I promptly got lost and distracted, but circled closer and closer to section C4 like a tied up dog circumnavigating its post, until I found section C39 next to section D3 next to a two-foot gap on the shelf without any books. The student from the front desk gave me exactly the look I was dreading when I came back to her empty-handed, but I successfully convinced her I wasn’t an idiot by showing her a picture of the book shelf. She told me to write down my email address and she would ask someone about it. A couple weeks later I got an email from a circulation manager.

“Your requested item is currently missing from our stacks.”

Lucky for me, somebody at the University of California scanned the whole thing at some point and I found it available to view through the HathiTrust digital library.

‘A HOAX AND AN INVESTIGATION’

Elmer Drew Merrill did not, in fact, “admit” the Pompeian mural featured a pineapple. Merrill said a reproduction of the mural by a much later Italian printmaker featured a pineapple, suggesting the artist mistakenly inserted a detail of unknown magnitude.

“There are, furthermore, no records in the extensive literature on Roman botany and horticulture of [pineapples] being present in any part of the Mediterranean,” Merrill wrote.

He even suggests original works may have been altered on purpose to embellish their significance and include details more recognizable to new audiences.

“They will have to give thought to the possibility that an artist involved in the Pompeii restorations in the past century perpetrated a hoax and an investigation of the pigments used might be in order,” Merrill wrote. “Then, too, there are the records of American maize found in mummy wrappings in Egyptian tombs which merely prove that some of the caterers of the tourist trade of the last century did not know their botany too well.”

A sketch of Austen Henry Layard by S.C. Malan c. 1850 (From Wikimedia Commons).

So what about Austen Henry Layard’s assessment that the Assyrian gypsum carving featured pineapples?

I asked Dr. Eleanor Wilkinson, a researcher who has studied Assyrian artifacts from King Sennacherib’s time.

“Since Layard published his accounts in the 19th century there’s been quite a lot of scholarship surrounding that issue,” Wilkinson wrote to me in an email. “Pineapples don’t appear in any other literary, architectural or artistic context during the Assyrian Empire... There’s really no evidence that I know of that ancient Mesopotamians were familiar with them.”

And Wilkinson offers a far more certain answer.

That pile of pineapples being delivered to King Sennacherib was actually a pile of pinecones.

“The general consensus among archaeologists and epigraphers is that those ritual cones probably came from a Turkish pine or Lebanese cedar, trees known to have been common in ancient Mesopotamia,” Wilkinson wrote.

Those Turkish pines and Lebanese cedars and their cones appear frequently in Assyrian art and writing, Wilkinson says.

A search of the British Museum’s online archives shows the trees in the backgrounds of gypsum reliefs carved during Sennacherib’s time, as well as written directions on using their needles in medicine. Even older Mesopotamian artifacts record an order for pine trees and a receipt of pine nuts. They have had lasting cultural significance in the area too; a conifer tree graces the center of the Lebanese flag.

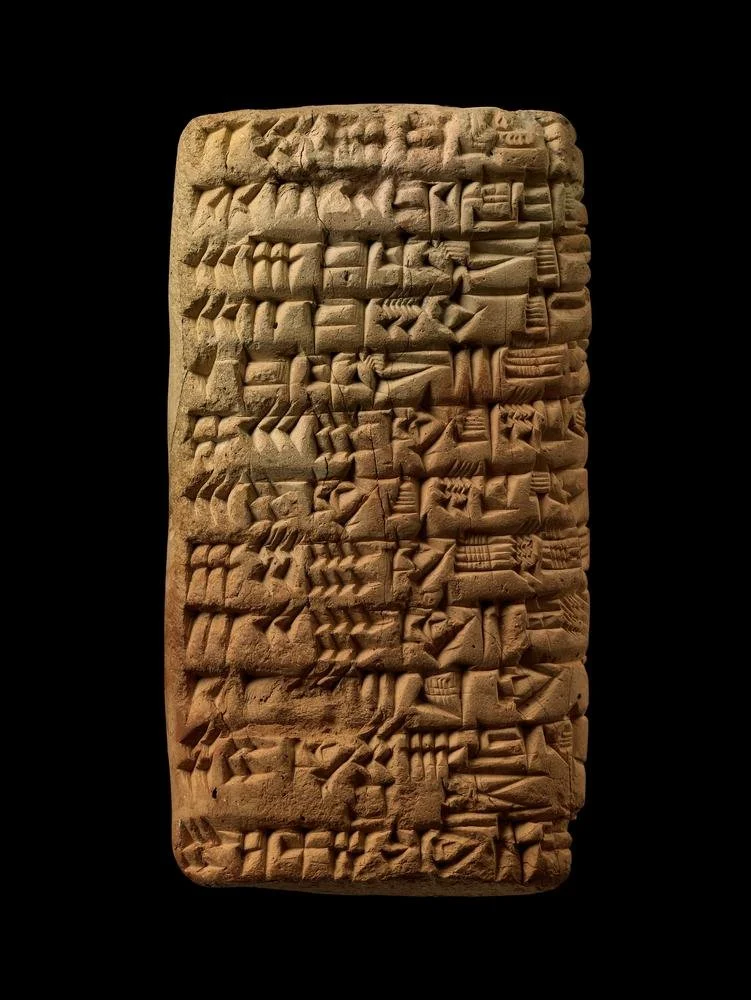

A clay tablet listing items in an order, including 1,400 pine trees, likely for shipbuilding c. 2100 BCE (From the British Museum).

The explanation also translates to Pompeii.

Pine trees and their cones featured in art across ancient Rome, and, according to Roman Catholic news website Aleteia, they have long symbolized life and rebirth. A courtyard in the Vatican, called the Cortile della Pigna, features a towering 2,000-year-old bronze fountain in the shape of a pinecone, cast right around the time that mural in Pompeii was assembled.

THE ROOT OF THE STORY

Modern mainstream history seems to agree there is not much evidence to suggest the existence of ancient global connections between what we today call the “Old World” and the “New World.”

The supposed appearance of the pineapple in ancient Pompeii, Assyria and Egypt does not prove otherwise. In fact, there are many such mistakes on the historical record. The botanist Elmer Drew Merrill points out an even more egregious one in his book after dispelling the pineapple.

“Certain pre-Spanish carvings in Central America were, at one time, described as representing elephant trunks,” Merrill wrote. “This would have been a sensational discovery, were it not that the figures showed only the long tail of the sacred quetzal bird!”

So maybe sometimes we squint at ancient weathered carvings or sun-bleached murals and see something familiar. And maybe sometimes those artifacts are deliberately exaggerative to flatter a king, or they were originally done by someone who didn’t know much about what they were depicting, and then maybe years later a “restorer” decided to put their own spin on it.

However, it is also worth noting Merrill dedicated an intense amount of study into whether pre-Columbus travelers from the Americas and Macronesia could have crossed the Pacific and traded food. In his research, Merrill believed he did find evidence of an ancient link across the world’s widest ocean. His evidence was in a food less glamorous than a pineapple, less likely to be first in line of tributes to a king, less likely to grace a mosaic.

The sweet potato.

To be continued...

###

THIS ARTICLE’S INGREDIENTS

Food In Antiquity: A Survey of the Diet of Early Peoples

Don Brothwell and Patricia Brothwell

Johns Hopkins University Press

Expanded edition published in 1998

The Botany of Cook’s Voyages: and its Unexpected Significance in Relation to Anthropology, Biogeography and History

Elmer Drew Merrill

Chronica Botanica Company

Published in 1954

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31822006538029&seq=219

Biography of Elmer Drew Merrill

The New York Botanical Garden LuEsther T. Mertz Library

Published in 2005

https://www.nybg.org/library/finding_guide/archv/merrill_ppb.html

Discoveries in the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, with travels in Armenia, Kurdistan and the desert

By Austen Henry Layard

Published by John Murray in 1853

“...should not hesitate to identify with the pineapple...” (pp. 338, 340)

Between Two Rivers: Ancient Mespotamia and the Birth of History

By Moudhy Al-Rashid

Published by Hodder Press in 2025

Email correspondence

Between Forrest J.H. and Eleanor Wilkinson

September, 2025

The story behind the Vatican’s 13-foot pine cone sculpture

Aleteia

September 2, 2024

https://aleteia.org/2024/09/02/the-story-behind-the-vaticans-13-foot-pine-cone-sculpture/

HathiTrust digital library

Gypsum wall panel relief

Southwest palace of Nineveh

Museum no. 124822

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1851-0902-4

Nineveh Medical Encyclopaedia

Clay tablet, Library of Ashurbanipal

Museum no. 131366

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1953-0411-201

Clay tablet

Museum no. 18390

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1895-0329-48

The British Museum

Online collection